A PRIEST COVERED HIS OWN COAT OVER HIS WORST ENEMY AND THEREBY SAVED NOT ONLY HIS BODY BUT HIS SOUL...

A man was thrown into the icy concrete "glass" of a punishment cell. The one already sitting inside, huddled in a corner, merely raised his head. For him, it was just another soul on death's doorstep, but for the camp system, it was a cruel irony: a former high-ranking NKVD officer who had approved execution lists was thrown to die in the very hell he had helped build. His cellmate turned out to be a priest, prisoner Arseniy.

The cell floor was covered in freezing water. The night promised a frost that kills the living. Avsenev, a former Chekist, an intelligent and once powerful man, knew the system from the inside. He knew that in the morning, two frozen bodies would be carried out. He was shaking. Not from fear—fear was too petty an emotion for the all-consuming cold gnawing at his bones—but from the animal tremors of death.

The priest in the corner didn't move. He simply looked at his new neighbor with a long, calm gaze, devoid of condemnation, hatred, or even sympathy. There was something different, something enormous, in that gaze that suddenly made Avsenev uneasy. He expected curses, malice, anything—anything but that deafening silence in the old man's eyes.

"Take off your clothes," the priest said suddenly, quietly, almost soundlessly.

Avsenev didn't understand. His thoughts were jumbled, frozen.

"Take off your clothes, I said," Father Arseny repeated. "Take off your shirt, lie down on the bunk, I'll cover you."

"Are you crazy, priest? We'll both freeze!" the Chekist croaked. Father Arseny rose slowly. He approached. His shabby padded jacket smelled not of camp rot, but of something forgotten—dried grass or bread. He began unbuttoning his quilted jacket.

This priest, one of those he despised, one of those he had sent by the thousands to similar camps, was now giving his life to him. Not for God, not for an idea—simply, routinely, like giving away one's last piece of bread.

And then the priest began to pray.

It wasn't a prayer of supplication. It wasn't a cry of despair. Avsenev, an atheist to the core, suddenly understood this with his whole being. From the corner where the old man stood came... warmth.

Not a physical warmth that could melt ice. Something else. Avsenev couldn't believe his own sensations. Time stood still in the punishment cell.

The sound of water dripping from the ceiling vanished. The whole world shrank to this concrete cell, where something impossible was happening.

The cold didn't go away—it was still all around, but it no longer penetrated. It seemed to envelop Avsenev's body, flowing around him, like water around a stone.

The Chekist saw the priest's back. He didn't move. He didn't kneel, didn't thrash about in ecstasy. He simply stood, and this incredible, protective power emanated from him.

Avsenev felt as if the walls of the punishment cell had become transparent, and beyond them lay not the camp yard, but something enormous, starry, and alive. He, who believed only in matter and directives, lay and looked at the back of the priest, saving him from the hell he had created.

And for the first time in his life, he wanted to cry. Without knowing how, he fell asleep.

In the morning, the bolt clanged. Two guards and the prison warden entered. They had come to collect the bodies. Their gazes were empty and familiar. But they stopped at the threshold.

The scene they saw was impossible.

On the bunk, covered with a quilted jacket, slept the former Chekist Avsenev, alive and well.

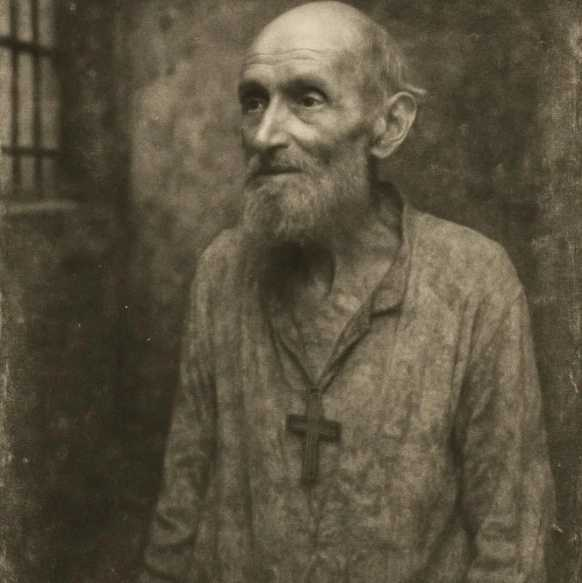

In the corner, with his back to them, stood Father Arseny. He was completely covered in frost. White as a salt statue, he shone in the dim light of the lamp. His hair, beard, shirt—everything was one glittering icy shell.

"This one," the warden nodded at Avsenev, "to the barracks. Alive, damn it... And the priest—to the morgue."

The guards approached the priest and roughly grabbed him by the shoulder to drag him away.

And then the old man slowly turned his head. He opened his eyes. And smiled.

The warden recoiled, dropping his cigarette. He looked at the priest's lively, clear eyes, piercing the icy crust, and his face twisted with superstitious horror.

He turned silently and left, muttering as he went:

"Take him... to the barracks too..."

Later, when the shocked Avsenev found the strength to ask the commander how this could have happened, the latter, without looking him in the eye, angrily said: "None of your business. Your priest prayed for you all night. That's why you survived. He prayed for you..."

This story, found in the unique collection of testimonies "Father Arseny," is not about physics and temperature. It's about how there is no icy hell, neither outside nor within one's own soul, where the heat of quiet prayer cannot reach, saving someone who has long since ceased to expect salvation. And showing mercy where, by all the laws of the world, only justice should prevail.

Author: Sergiy Vestnik

"She's only fourteen! What if she can't bear Napoleon a child in the first year of marriage?" Empress Maria Feodorovna asked. "Then he'll want to divorce her or have children at the cost of her honor."

Alexander listened thoughtfully to his mother. Napoleon had offered Poland if he were allowed to marry Grand Duchess Anna Pavlovna. But knowing the French Emperor, the Russian Tsar doubted anything would come of his proposal. Napoleon always turned situations to his advantage. If their relationship with him worsened even further, his sister could find herself in a very difficult situation.

"If you agree to the marriageu, you will ruin Anna."

"Calm down, Mother," Alexander replied softly. "Only you can decide her fate." I will submit to your decision.

Anna Pavlovna was born in January 1795. She was the eighth child of the Grand Ducal couple Maria Feodorovna and Pavel Petrovich. Empress Catherine, upon learning of the birth of her sixth granddaughter, sadly remarked:

"There are so many girls, we can't marry them all off!"

The Empress never learned of her ...

A big shout out to the people who follow me. Unfortunately I’ve had to leave Russia. It became impossible to receive any funds from the US. I am currently living in Batumi, Georgia.

This is my family in the living room of my apartment in Kimovsk, Russia. I am a disabled Vietnam veteran. Seventy six years of age. My son Aleksandr (left), and my granddaughter Dasha (center) look in on me. Here, I had hoped to live out my retirement years.

In Kimovsk is where my apartment is located. Last summer I visited my granddaughter who lives in Tula. I stayed there for two months. I became very familiar with the city of Tula.

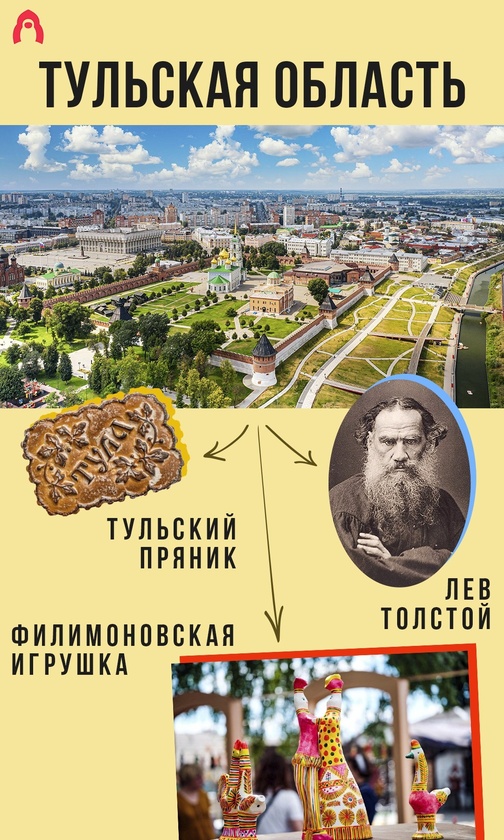

Tula Region is one of the industrial centers of Russia, famous for its long-standing traditions of weapons and samovar production. Here are three more important symbols of this region.

1⃣ ЛЕВ ТОЛСТОЙ (Leo Tolstoy)

The famous Russian writer was born on September 9, 1828, on the Yasnaya Polyana’ Family Estate near Tula. He spent a significant part of his life there, creating his main novels, including ‘War and Peace’ and ‘Anna Karenina’. His body was also buried there.

2⃣ ФИЛИМОНОВСКАЯ ИГРУШКА (Filimonovo toy)

Whistle toys in the form of people and animals with conical heads began to be made in the village of Filimonovo near Tula in the 16th century. After the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, the craft died out for a while, but was revived in the 1980s.

3⃣ ТУЛЬСКИЙ ...

I am decorating my living room with items that are truly representative of the Middle East.

I have a samovar from Tula, Russia. I bought it at a shop that specialized in samovar and was located in the Kremlin. My granddaughter helped me pick it out.

I have two Russian tea glasses with comemeritive holders.

I don’t smoke but I have a hookah. It is very decorative in bright red.

I have a porcelain fruit dish on a pedestal. It is a red and gold pattern.

I have a five branch candle stick for the center of the dining table. It’s useful when the electricity is not available.

I have two floor lamps. One is of Morocco design.

A print of a painting of a Venisen canal scene hangs over the sofa which is classical Georgian.

Three nesting tables and a coffee table and a large vase full of roses.